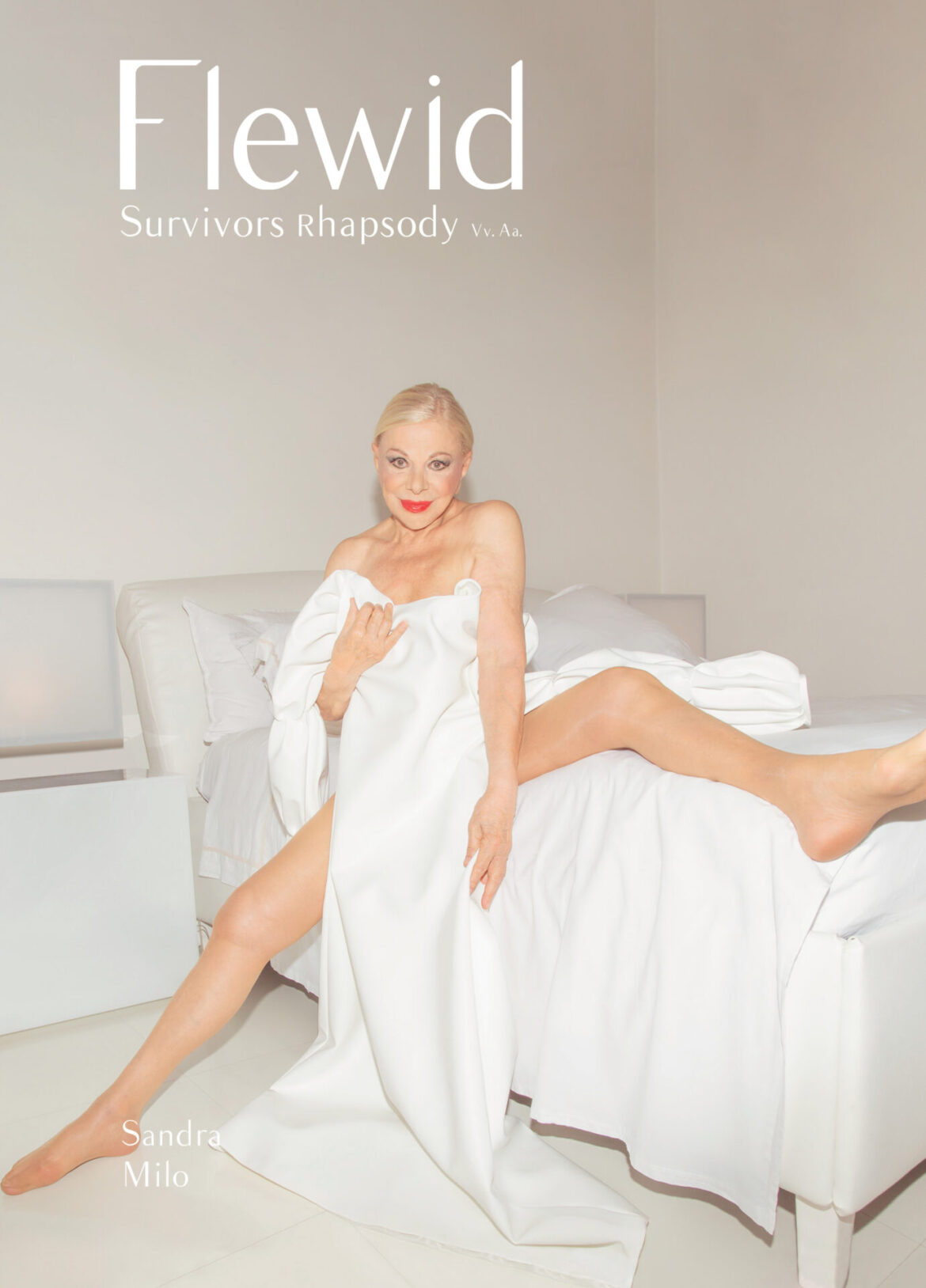

FLEWID VOLUME 4

Styling Emi Marchionni

Interview Giuppy D’Aura

TODAY WITH FLEWID, WE MEET AN ACTRESS FOR WHOM THE WORD DIVA IS CERTAINLY NOT WASTED. THE UNDISPUTED QUEEN OF LIGHTNESS AND SENSUALITY, MUSE OF DIRECTORS SUCH

AS FELLINI, ROSSELLINI AND PIETRANGELI, AND CAPABLE OF GIVING PERFORMANCES ON ANY TYPE OF PLATFORM AT ANY AGE: THE CINEMA SCREEN, THEATRE, TELEVISION AND EVEN THE WEB. WHAT YOU LEARN FROM A BRILLIANT MIND LIKE SANDRA MILO’S IS THAT FRIVOLITY AND PROFOUNDNESS ARE NOT ENEMIES, BUT SISTERS AND THAT ONE NEEDS THE OTHER TO FUNCTION PROPERLY.

On your Instagram profile, at the beginning of the pandemic, you spoke at length about your experience as a girl during the war, drawing a parallel between the two. What did that experience teach you that can be useful today? We always have the feeling of being eternal and untouchable. But the lesson that has remained with me from the war is that everything is possible, and we must live the present in all its intensity.

You were lucky enough to see your career flourish in the years in which Italian cinema was watched and admired around the world, acting for maestros such as Pietrangeli, Rossellini, Risi and above all Fellini. How did Federico Fellini enter your life?

Fellini was introduced to me by Ennio Flaiano. At the time I was still a girl but I must say that he struck me immediately. He was handsome, tall dark and with bewitching eyes. That first image remains with

me still today. Then I happened to make a film with Rossellini (Va-nina Vanini, 1961) which was received terribly at the Venice Film Festival. Today it is considered one of Rossellini’s masterpieces, but at the time I was forced to abandon my film career temporarily. Fellini, however, really insisted I be in 81⁄2 (1963), even though I was against the idea. In short, he was right because it changed my life. After that film ever yone wanted me!

You could say: a star was born!

Could you paint a portrait of Fellini the man and the filmic imager y of Fellini?

First of all, he was a man full of love and someone who had great respect for feelings. For example, although his films are imbued with sensuality and eroticism, there’s also great demureness in them. Never a kiss, never an explicit sex scene. I’ve always thought this was due to the respect he had for a sphere as essential as the sexual one is for human beings.

Of the films you have made, for which one do you have the fondest memory?

I hate some of the films I’ve made; I adore others. Perhaps I gave the best of myself in The Visit (1963) by Antonio Pietrangeli. The film is a very delicate and intimate portrait of love, but above all of the feminine search for love as a gift.

What do you think about the way cinema has changed since then?

There’s one thing that always embarrasses me when I make a film today, and it’s the fact that the director is never present. He is in another room to watch the scene on a screen. In the past, the director was always there in front of you. If, for example, there was a close-up, he was right there with you, not only to check that it looked good, but also to convey his feelings to you and I think that this was transmitted through the screen. Today, even the act of making a film seems to have become a bit dehumanized to me. Technology has taken over everywhere.

We saw you at the forefront of the fight for Italian cinema (you were also received by Prime Minister Conte). But do you see any worthy heirs of Fellini, Rossellini and Risi?

You know, I think the essential thing in life is change, so it’s difficult for me to make a qualitative comparison. There were better things in the past, in some aspects, and today in others. There are many young Italian directors who could be considered the heirs of the greats of the past. Some also have a great poetic sense of life, but I’d prefer not to name names so as not to offend anyone.

As you know, our magazine, Flewid, is based on the concepts of inclusion and respect for

all identities, themes that are, unfortunately, increasingly less obvious today. How do you think we can work to build a society that is more egalitarian and respectful of all differences?

I don’t think inclusion is or should be a difficult thing. Today there’s a rush to say that there are no races and no differences, but I don’t think this is the point of the matter. In nature there are thousands of differences between species and also between humans, but this shouldn’t prevent us from respecting and loving each other. I’m a Christian and for me we are all children, equal before God. Discrimination just doesn’t make any sense to me. I think everyone should always be loved, from an early age.

Ever yone?

Yes. I’ll give you an example: if I find a person unpleasant, because he is rude or impolite, I immediately imagine him as a child and I think of when his mother cuddled him and he had faith in humanity. I tell myself that at one point he too was a wonderful person and trusted in life, and so he immediately appears to me in a different light.

Do you mind if I ask you what you are working on?

Of course! In the autumn I’ll be at the theatre with a work about Federico Fellini, and then I’ll do another show I particularly hold dear: Ostriche e caffè americano, in which I play a drag queen who runs a group of drag queens. One day a new performer arrives at the club and from there the plot takes unexpected and intense twists and turns. Just thinking about the story makes me want to cry. For me this is a show about the miracle of birth and how it can come from many different places while always being worthy in the same way, come and see it!