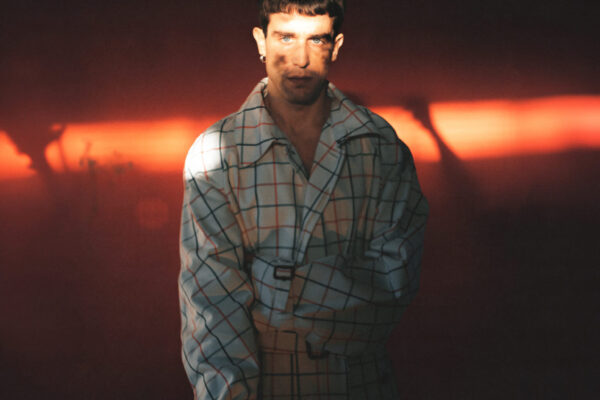

FLEWID VOLUME TWO

Photographer: Efisio Marras

Fashion Editor: Antonio Marras

Writer: Giuppy D’aura

Antonio Marras is not only one of the most refined and unique designers of his generation, but also a man of extraordinary intelligence and culture. He has often anticipated themes that fashion has only gone on to develop later – like the almost obsessive insistence on embellishment when everyone thought of working on subtraction – and has always created his collections as if they were literary texts in which he could play with grammar and revolutionize it. But for Marras, as for any great writer, the innovation of a language can never exist without the perfect knowledge of its rules, because one can only destroy a code if first one has a perfect command of it. Antonio Marras speaks as he designs, and he expresses himself as he sews: his answers are always accompanied by meticulous and precise lists, words are possessed rather than sought and ideas are so thoroughly thought through that they can never be expressed in a few words. In the following interview we have tried to enter his world, his cultural references and his geography, to better map the genesis of his clothes.

My personal impression on seeing your collections (I am Sardinian, too), is that at the origin of each of them there is a memory of the past, a piece of clothing found in the back of the closet, or a ancient object that – like the madeleines in Proust’s Recherche – generates an associative chain which is expressed in the clothes that you create. Am I wrong? How do you create your Antonio Marras collections? No, you’re not wrong, in fact, you’ve grasped the concept.

For me, designing a collection is like writing, telling a story. The very beginning is always a story. There may be many narrative cues and they trigger visual analogies, original images, sudden meanings. A character, a person met by chance, a story, even a trivial event, an image, an object, a figure, a verse, a song, some music, a letter, a film, all these things can set visions in motion and I always try to grasp the messages and translate them into signs. I love giving voice to apparently silent things, so that they become “rags that speak”.

It’s difficult to explain how an idea is born; it’s difficult to say how a creative process is born, difficult to rebuild the actual process. It often follows irrational paths, yet always new ones.

There’s never anything preordained and everything can be turned upside down. Inspiration is a mystery. Images arrive without me looking for them and they are stored in my mind in many drawers. From these half-open drawers, at the right moment, the collection comes out, recalled by urgency. Every collection is like a chapter in a bigger story, a self-contained chapter in itself and one that works as a separate story. It dialogues with those that preceded it but it is absolutely original, unique, a weave made up of the past with its own references.

We understand that Antonio Marras is a designer who starts from emotion and intuition, in short…

Inspiration and intuition are not enough; it takes a great amount of work.

Teamwork that expresses itself in a complex language. The word, the gesture, the sound, the music, and also the scenography must visualize every thought. If even one of these elements were missing or clashed with the others, everything would be askew Everything is joined with everything else. A comma, a full stop, a pause, a detail, a thread may take on meaning, and so give a message. The fashion show is the topical moment, the crowning of a beautiful labour, which requires great energy. It represents the climax of all the work.

What is the value of the present if we must always refer to a memory of the past to create it?

A-I don’t know! I live in houses full of furniture, objects and clothes. I collect, amass, combine everything I find.

Old furniture, clothes, objects in the attic destined to be forgotten in attics, in spare rooms, in markets, pressed by the urgency to breathe, and to come back to life and tell their stories attract me. Recycling everything and not throwing anything away is something natural, innate for me, because nothing is destroyed but everything is recreated. I’m attracted by what has a hint of shadow, of the past, of stolen, denied lives.

In particular, used objects that are worn, broken, torn, thrown away, useless and dirty. I can’t help thinking about who has worn these clothes, used these objects, read these books, has stopped to look at these paintings, or who has spent a lifetime at these tables or filled a cabinet with their precious objects. Destroying them, or worse, forgetting about them seems like an outrage, a sacrilege to me: almost as if I erased the presence of so many existences prior to mine. Reinterpreting them is a way to give them another chance and, at the same time, to honour the memory of those who have lived before me, through their personal effects.

In your collections you mix elements that are traditionally thought to be poles apart, for example the Prince of Wales sewn together with lace or sports sweatshirts that become dresses because embroidered tulle is added to them; if it’s true that today this has become common practice (Michele’s Gucci comes to mind, for example), it gives me the impression that you have been an absolute precursor, where did this drive to marry contrasting elements come from?

I’m attracted by the poetic language that rejects rules, violates codes, frees all the senses and gives voice to the inexpressible. I work with “rags”, the poet with words; he composes texts, I weave textiles. Textiles and texts both refer to a common origin: weaving, spinning yarns. Both are the result of intertwining. I feel very close to the linguistic gap from the grammatical norm, the deviance from everyday language, the free use of words that are combined in an unusual way, creating unexpected plays on words and oxymorons.

“The stars are buttons of mother of pearl and the evening is cloaked in velvet”, that is, after all, what I do with “rags”.

So how does poetic language apply to fashion?

I work on accumulations and stratifications. The assemblage opposes subtracting and reducing. It is a struggle against platitudes, banality, and the commonplace. Excess and eccentricity win in my collections. We need the system and we need excess, but I prefer excess. The system is a closed order that demands rigour. Excess break the order, all the rigour and produces something new. I have the soul of the collector. Not throwing anything away and recycling everything, is something instinctive, innate, and natural for me.

Perhaps it’s not a coincidence that you come from a crossroads of cultures like Alghero, an exclave of medieval Catalonia in Italy, what influence has this had on your approach to creating?

Alghero, where most of my work takes place, is an old fortress shaped like a city, which still preserves its past as a Catalan city, unique in Sardinia and Italy, in its language, traditions and culture. Alghero has a mysterious charm that comes from mixing: a mixture of languages, cultures, stories, traditions, customs, thoughts, contaminations and stratifications are the things that make it so special.

A past of a Sardinian city conquered by the Catalans who drove out the inhabitants and repopulated it and gave it the privileges of being a Royal City and, therefore, a different identity to the Sardinian one.

But then the Sardinians returned and today Alghero is a composite reality, alive, that wants to defend its history, its language, its culture and its territory. At the same time it is open to new ideas, to what is different, to the foreigner. An accommodating city, perhaps too much so, as is customary in ancient places like Sardinia, Greece, and among the peoples of the Mediterranean.

Fortunately, Alghero still preserves its uncontaminated environmental heritage and a landscape of incomparable beauty with its dense, fiery, endless sunsets.

And do you live inside the walls of Alghero?

I live and work in the country, in a house-studio in the hills, between olive trees and the sea, my personal haven. For me, the boundaries between personal and working space are very blurred. Here designs and solutions are tested that will then be reproduced on a large, industrial scale; this is where I started my Linea Laboratorio, which encapsulates and summarizes my modus operandi: my work on vintage, deconstruction and re-assembly, experimentation, and research.

What is harmony for you?

An oxymoron. It is an oxymoron, the one who harmonizes, reconciles opposites, makes the global local and the local global, giving shape and harmony where there is disaccord, capable of generating unknown orders and creating new kinds of beauty, new messages that are addressed to everyone and decipherable by everyone.

And what do you think identity is?

It’s not easy to talk about identity nowadays. In a globalized world, decidedly moving towards homologation, this word, which is used and abused, now seems to be struggling for breath, losing its original meaning. Identity refers to a broad area of meaning; a coincidence of elements, a set of distinctive characters, a sense of belonging, self-awareness, sharing, and acknowledgement of things or individuals as separate entities and opposed to each other. It’s a term that, in various contexts, takes on specific meanings and is endowed with connotations.

Science and technology have broken down borders, pulled down barriers, juxtaposed and mixed peoples and continents. Indeed, the contact/clash with others is the defining feature of our time: the history of groups, peoples, and ethnic groups is intertwined with other histories and becomes increasingly complex. In this context, the desire to affirm the right to defend and safeguard one’s identity and to value diversity as a factor of wealth and cultural heritage to be preserved and made known is gaining ground. For me, identity is not a static fact, nor is it pure memory, but rather a continuous construction, made up of distinct realities. We and the other, separate but at the same time bound together, in a process where constant exchange nurtures and keeps alive, giving rise to signs of identity.

How would you define style?

Style for me is something innate, personal. It’s the ability to dare, naturally and freely, to have the courage to test and transgress rules, violate codes of conduct, prefer stepping away from the norm to following the norm, even if it be in just a small detail. One has style when one isn’t afraid of excessiveness and eccentricity triumphing over the platitudes and banality of common dress sense. One has style when one doesn’t conform to the prevailing dictates but seeks out the errors. One has style when one has that Je-nesais-quoi or that presque-rien which is, after all, the essence of everything.

If you were to name great fashion creators in the past or present who have inspired you, who would you name?

Paul Poiret. His father was a textile merchant like my father. And I admire his revolutionary nature, his passion for Orientalism, for folk, for popular Russia and especially for his beloved Denise.

Can you give me the names of your contemporary colleagues you admire?

Definitely the three Great Dames of fashion: Rei Kawakubo, Miuccia Prada and Vivienne Westwood.

What inspired your latest, very elegant A/W 2018 collection?

I was on the internet and I stumbled upon a certain John Marras, a miniaturist, who at about the end of the eighteenth century left France to go to New York and open a shop. Patrizia thought he might be one of my ancestors and pieced together a family tree.

The story “For Grace Received” speaks of journeys, shipwrecks survived, encounters and love.

Now a question that needs to be asked: what do you think of the current evolution of the fashion market (the fragmentation of customers into many niches, the rise of the millennials, the cardinal importance of sportswear, etc.)?

Everything has changed in a world where Dior makes T-shirts and Zara evening dresses. I don’t understand it, but I acknowledge it. You see, I don’t pursue fashion or follow its whims. I don’t align myself. The true contemporary is one who does not conform perfectly to the dictates of these whims and I believe that this is what gives relevance to creations. I look at fashion from a sort of distant perspective that, perhaps, allows me to see it in its entirety. It fascinates and seduces me, the ludic dimension it has, its thoughtful lightness, its grammar, the code that is made to be broken, violated in the continuous tension in search of a perennially new beauty.

What relationship do you have with social networks, which today seem to be the main medium for communicating fashion?

As a devourer of images, I love Instagram. Its speed fascinates me.

But that’s all. I’m not sure that social media will remain the main medium for communicating. A little like when it was thought that ebooks would replace the printed page. It hasn’t happened and it never will.

Are there any materials you particularly like to work with?

A-I love fabrics and I’ve always had a special relationship with them. Voile, satin, organza, chiffon, crepe, taffeta, muslin, viscose, cady, georgette, batiste, duchesse. Transparent, airy, light, fluffy, rustling or heavy, full-bodied, sumptuous, robust. All of them! I’d say all of them.

I’m enchanted by the interplay of the warp, the weft, and the trama that create decorations, designs made visible by the reflection of light that gives life to magical contrasts of shininess and opaqueness.

I’m also fascinated by temporal contamination, between the past and present, between epochs in opposition.

Recouping, mixing, assembling, changing, giving them new meanings, and transforming them in a continuous flux and flow: this is what I do.

Do you have a silhouette or a recurring item that is particularly important in your production, such as the new look for Dior, the tweed jacket for Chanel, or the deconstructed jacket by Armani?

The Kimono. The Kimono gave me the idea of reinterpreting prints, fabrics, and colours, of exploring the traditions of the East, mixing them and melding them with those of the West. I compared the traditional Sardinian dress with the Kimono and tried to reconcile their differences and create a synthesis between these two very distant cultures.

Over the years fashion has tended to favour the structure of clothing (the 90s of Helmut Lang and Jil Sander for example), now decoration (in the case of today’s Gucci or of some old, beautiful Ferrè collections). If we wanted to have fun and divide the world into two, do you think you belong more to the school of decoration or to the one of structure?

There is no doubt: my style is decoration. Perhaps I’m fascinated by Sardinian dress for its extraordinary variety, its structural, decorative, and chromatic elements, and for the meaning it has in terms of ethnic identification.

Everything in traditional Sardinian clothing speaks and communicates; items of clothing, personal adornments, and embroidery all express the social dimension of the people who wear them.

Decorative forms are loaded with symbolic meaning; Filigree jewels, amulets, lace, and embroidered canvases, the asymmetries, dissonance, the inlays of both precious and poor fabrics, give life, when mixed together, to ever new solutions, to extremely topical creations, in which history and contemporaneity coexist.

What sort of literature does Antonio Marras like?

I’m a little disorderly and inconsistent. I read, above all, works related to the collections. For each one it becomes a total immersion in history, in art, in poetry. Sometimes I have lived with men and women from the Bloomsbury Group, even engaging in dialogues with Virginia, Vanessa, and Vita and surprising them in their fascinating lives, sometimes I immerse myself in Calvino’s novels to search for the traces of my mother whom I love so much.

I also read during my travels, when I’m not doodling in a notebook. I like poetry, which is also like looking at an image. I loved Something Written by Emanuele Trevi, a fascinating work starting with the cover itself that has a photo that captures Pasolini and Laura Betti at the peak of their splendour. I love the torment of A Love Affair by Dino Buzzati, as well as Michele Mari’s short stories and those by Testori.

I often let Patrizia, the real devourer of books, advise me.

And then there is a book that I read and reread, a crazy love that still hasn’t abandoned me: Spoon River Anthology by Edgar Lee Masters, the book close to my heart that takes bleak lives and turns them into poetry. A read that always envelops me and transports me to that hill.